Top 3 Vitamins We Love for Skin Health

Learn why we love Vitamin B3, Vitamin C, and Vitamin D, and how each can make a difference in your skin health.

Dr Michael Rich is a specialist dermatologist who has been performing tumescent liposuction for over 30 years. Find out if Liposuction is suitable for you at ENRICH Clinic.

At ENRICH Clinic, we have a wide range of dermatological and cosmetic body treatments tailored to individual body and patient needs.

At ENRICH Clinic, our treatments are performed by our medical team consisting of doctors, nurses, and dermatologists and are tailored to each patient’s skin health needs.

ENRICH Clinic is committed to your skin health and well-being with a range of dermatological & cosmetic treatments tailored to the individual. Our treatments are performed by our medical team consisting of doctors, nurses, and dermatologists.

Skin health is essential for everyone. ENRICH Clinic has a wide range of technologies and dermatological solutions to help you achieve your skin care goals.

Goosebumps are a way for our bodies to keep heat in when we are in a cold environment, but they also serve other purposes – if you’ve ever been scared and gotten goosebumps, you’ll know the feeling.

Goosebumps are a way for our bodies to keep heat in when we are in a cold environment, but they also serve other purposes – if you’ve ever been scared and gotten goosebumps, you’ll know the feeling.

These tiny little bumps are the muscles at the base of our hair follicles contracting to raise the hair and close the follicle. This stops heat escaping, but also protrudes the hair into the environment maybe for sensory reasons or when we used to have more body hair, to make us look bigger to a predator.

If there is no hair in the follicle, the action still exists, for example if you wax your legs or arms, you can still get goosebumps.

Read How skin works – the layers

Some people respond to nails down a blackboard with goosebumps, when listening to evocative music, or experiencing certain positive feelings. Some people are able to get goosebumps on purpose, with the most common area to get goosebumps being the forearms, but the neck, legs and other areas of skin with hair on them react too. A classic is ‘the hair stood up on the back of my neck’ when something scary was just about to happen.

Goosebumps can also be a sign of disease, including epilepsy, brain tumours or a condition known as autonomic hyperreflexia. Drug withdrawal can also cause goosebumps.

The medical name for goosebumps is cutis anserina or horripilation (based on horror, as in, scared). We experience goosebumps only when we are cold, or have strong feelings – fear, euphoria or even during sex. We may get goosebumps when we are stressed, as part of our natural reflexes. This reflex is called piloerection (meaning a stiff hair), and occurs in many animals, not just humans. A wonderful example of an animal that acts like this is a porcupine, with quills raised when the porcupine feels threatened. A sea otter also has this reflex when it runs into a shark, and you may have noticed that even cats do this when they are scared.

Most birds, when plucked, share the same ‘goosebumps’ skin, and this word, or some other bird’s name or reference to, is used in many unrelated languages for the same phenomenon – Japanese, Hungarian, Spanish, Afrikaans.

*With all surgeries or procedures, there are risks. Consult your physician (GP) before undertaking any surgical or cosmetic procedure. Please read the consent forms carefully and be informed about every aspect of your treatment. Surgeries such as liposuction have a mandatory seven-day cooling-off period to give patients adequate time to be sure of their surgery choice. Results may also vary from person to person due to many factors, including the individual’s genetics, diet and exercise. Before and after photos are only relevant to the patient in the photo and do not necessarily reflect the results other patients may experience. Ask questions. Our team of dermatologists, doctors and nurses are here to help you with any of your queries. This page is not advice and is intended to be informational only. We endeavour to keep all our information up to date; however, this site is intended as a guide and not a definitive information portal or in any way constitutes medical advice.

"*" indicates required fields

Combining Dr Rich’s dermatological skill with his knowledge of restorative skin regimes and treatments, the ENRICH range is formulated to help maintain and complement your skin. Our signature Vitamin C Day & Night creams are now joined by a Vit A, B,&C Serum and a B5 Hyaluronic Gel, both with hydration properties and much, much more.

Learn why we love Vitamin B3, Vitamin C, and Vitamin D, and how each can make a difference in your skin health.

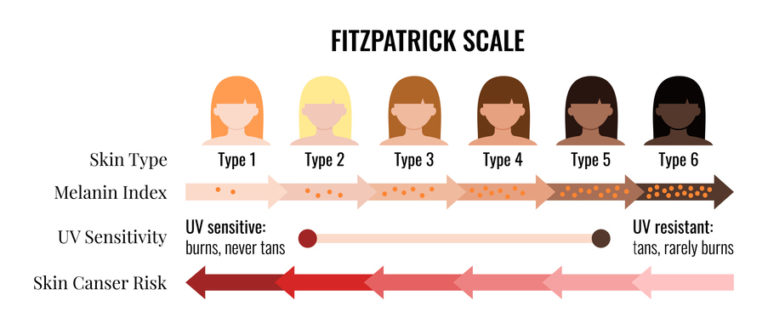

Learn what the Fitzpatrick skin type system is and why we always check your skin type before any procedure at Enrich.

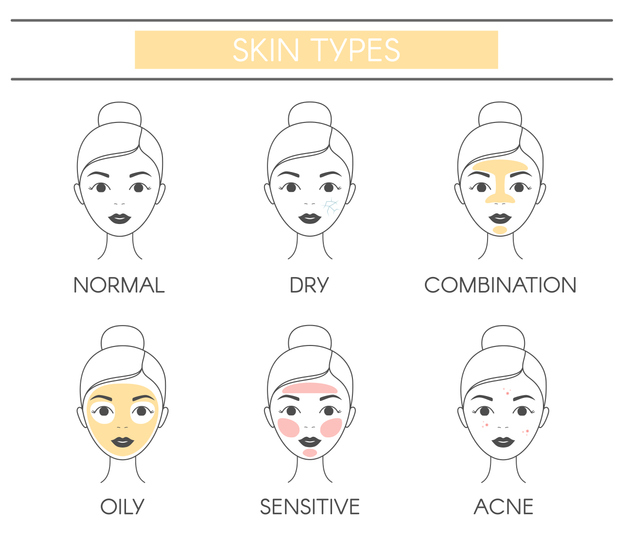

We address skincare trends & debunk myths while also providing guidance on products & treatments you should avoid based on your skin type.

Makeup can temporarily make your skin look flawless & dewy, but it merely masks imperfections & may not address the root causes of your skin concerns.

Subscribe to the ENRICH newsletter and receive latest news & updates from our team.

Enrich Clinic acknowledges the Traditional Lands of the Wurundjeri Woi Wurrung and Bunurong peoples of the East Kulin Nations on which we work and trade. We pay respect to their Elders past, present and emerging. We extend our acknowledgement and respect to the LGBTQIA+ community who we welcome and support. Read our full Acknowledgement Statement here